Glycogen, Lactic Acid, Rigour Mortis & You. Aging Meat. Hang Meat.

You have found your prey, put it down and are ready to start processing it. What happens next is going to directly affect the end product – the taste, the tenderness, the quality of the meat. Are you doing the most to maximise it? You hang meat.

The treatment and timing of working with a fresh kill is yet another subject that sparks many varying opinions and ultimately disagreements. I guess it’s similar in the way that some people still believe that the majority of game meat is always going to be strong flavoured and tough. It certainly doesn’t have to be.

The first venison I was given I totally ruined in the preparation and cooking – more correctly, I took it home and cooked it within ten hours of the animal being killed – it was tough. However, a quick look online revealed I had really just committed a basic but common mistake – I had cooked it bang in the middle of the process of rigour Mortis. When the meat is probably at it’s toughest. But what exactly is rigour mortis, what causes it and how do we manage it to ensure we get the best out of our meat?

In it’s simplest form, we can consider oxygen to be responsible for muscles being able to relax. Specifically, Oxygen is required for the production of Adenosine triphosphate, which causes the myosin (thick filament) to release the actin (thin filament) of a muscle, allowing the muscles to separate and ‘relax’ or expand. No Oxygen (as in, no longer breathing) means the chain of events required to allow a muscle to relax disappear and the muscles start to bind and stiffen. The time it takes the body to lose the last of it’s oxygen stores is the time it take for rigour mortis to set in. Once set in, it requires another chemical reaction to take place to release again.

At the same time a chemical process is causing the body to stiffen, a secondary process is underway.

Glucose in the muscle starts turning into lactic acid. This results in a change in internal pH levels and in turn affects the speed of tissue breakdown. The speed of this process directly affects the resulting meat. Too much lactic acid (generally caused by a high stress death – for example a long chase or a long track after a wound) and you can end up with pale, soft meat, too much and you get darkened, firm and dry meat (long term stress – i.e. poor condition animals).

The goal then, from both a moral and quality standpoint? A quick, unexpected death. This results in a controlled and gradual breakdown.

The breakdown is also what ultimately ‘releases’ rigour mortis. The myosin starts getting broken down in turn releasing its grip on the actin and therefore letting the muscles expand again, ‘relaxing’ the muscles. They key then, is to find the point where the muscles have relaxed, but the decomposition of the body isn’t at the point where health or taste concerns kick in.

It’s all about timing.

In a deer, dependant on temperature (warmer can speed up the process), size and general condition of the animal, rigour mortis is expected to set in with six to twelve hours – and will be gone within twenty four.

Everyone has their own rules on this one – but one seems fairly constant – butchering your animal while it is in the process of rigor mortis will result in tougher meat. It’s generally considered better to wait until after – also known as letting the animal ‘set’.

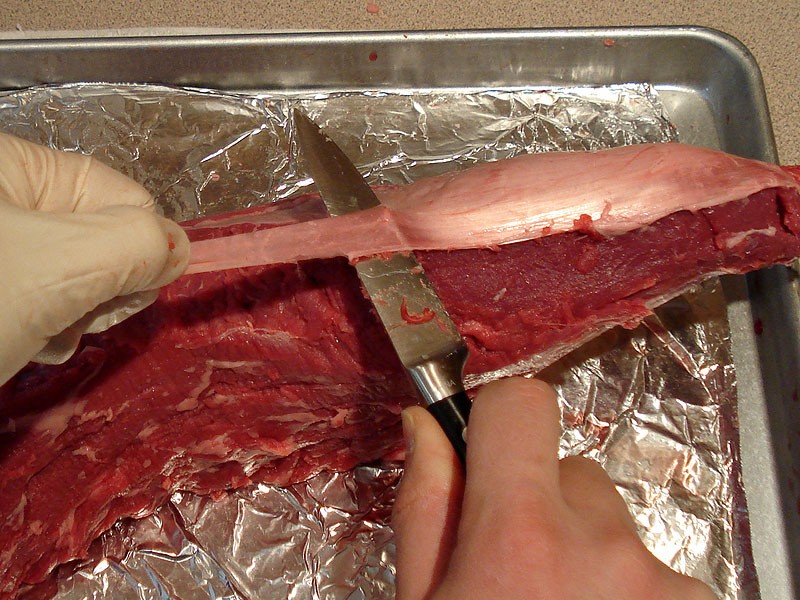

The ideal situation would be to field dress the animal immediately, removing the internal organs and starting the process of cooling the meat down. This is because, as above – temperature effects decomposition rates – the warmer the faster – and we don’t want the animal starting to decompose in a negative way, especially when only certain parts of the animal (internal) are doing so.

Then, skinning the animal before too much cooling (generally easier to do) and then hanging the animal to allow it to completely cool and set. In an ideal world – this would be in a temperature and humidity cooled chill room. Though this obviously isn’t going to be practical in the back country.

Once the meat is set – you can decide to either let the carcass hang to allow the flesh to further tenderise as the enzymes further break down the bonds within the muscle, or you can butcher and store the meat.

Hung and then packed. The wonders of using a butcher!

Hang or Freeze?

In an ideal world, we would all have chillers out the back of our places. In the real world, particularly for urban hunters like myself, we don’t have somewhere we can leave an animal hang for a couple of days.

Ideally, consensus is, would be to leave the animal hanging for around a full week before processing. The goal being to find that sweet spot between stiff and pongy. ‘Aging’ an animal this way helps with tenderness and improvement of flavour. Yes, we want our meat in an initial state of decomposition. But not what we would generally consider ‘rotting’.

However, if we don’t have the facility to hang our meat in a chiller there are still options.

Some people get themselves an older standing fridge – pull the insides out and use it as a mini-chill room. If you do this – make sure the fridge doesn’t have a ‘defrost’ mode – as this will not do the meat any favours.

Finally. If all else fails – you can resort to simply processing the meat, cutting it into steaks/roasts, and letting it age in the freezer. Yes. Meat will age in the freezer. I know of one guy who all but rotates his meat seasonally. What is in the fridge now, won’t be even looked at for at least six months.

Two of my favourites.

Interestingly, this whole article came from the question –

“If I want to process the animal in the field, how much can I do without diminishing the quality of the meat?”.

To me, the concept of carrying out a field dressed animal, bones and all, isn’t that smart. I personally am not going to use the skull, ribs, bones – so why expend energy carry it?

What my consideration was – is basically – can I kill it, gut and skin it and quarter (or even bone out) that animal before rigour mortis sets in and how will it effect the meat? Well – obviously I can. More importantly – does doing it this way loose anything in quality to hanging a carcass for a couple of days first?

Theoretically, as long as I am relatively swift, I shouldn’t experience any additional shortening – provided I do most the work before the oxygen levels drop enough to start having the meat stiffen up. It might be the case though, of only cutting into major sections – then I still have the option of dry aging some large sections. That process being another article.