What makes meat juicy and tender?

TLDNR Version: Slow cook tough cuts with some wine. We already know this. But are you interested to know why?

Multiple factors come into play when we try to understand what makes the meat juicy and tender. Nothing beats a piece of meat that nearly mounts in your mouth but retains that juicy, flavoursome texture. This is influenced by the cut of meat and how long it is cooked. In the case of cut choice – the more a particular part is used by the animal, the more muscular it is likely to be – which means the presence of more connective tissue.

What is Connective Tissue?

Muscle fibres are bound together in collections of protein by connective tissue – in addition, each collection of muscle fibre is additionally covered in a sheath of connective tissue.

There is two main types of connective tissue, Collagen and Elastin.

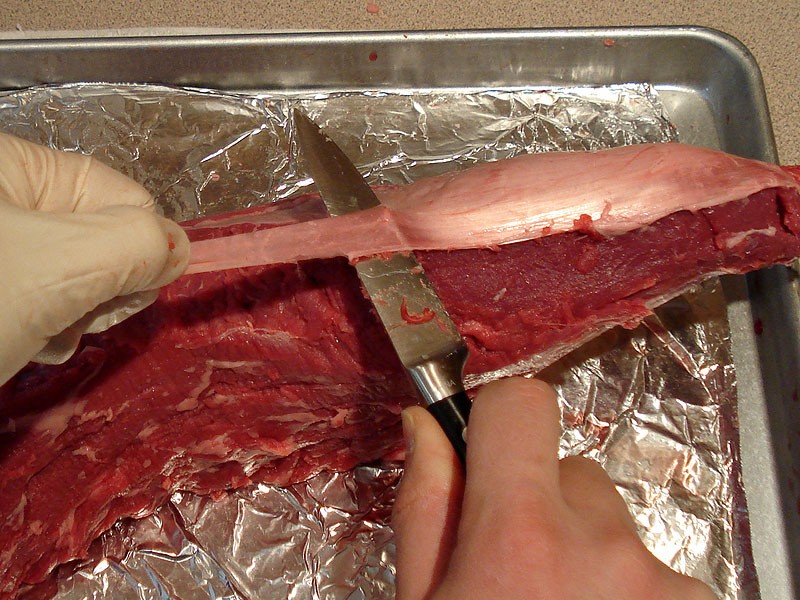

Collagen is the white ‘silver’ that most of use know due to having to cut it off our cuts of venison. While a cut with a pile of Collagen in it may seem to be a ‘junk cut’ – in reality, it also gives us the opportunity to create some of the more silky, ‘pull-apart’ meals for a simple reason – Collagen dissolves in moist heat. Meaning, slow, moist cooking breaks Collagen down into Gelatine and Water. Both things that can go a long way to making meat seem juicy and tender.

Elastin, however, is not so easy to get rid of. Elastin, yellow in appearance, forms primarily in older animals, strongly being the reason that an old stag can be considered chewy as all hell. Unfortunately, it doesn’t break down due to cooking, so needs to be dealt with by either cutting it away or mechanically breaking it up.

How do we break down Connective Tissue?

The goal then is to break down or reduce the connective tissue in order to make the meat more tender. More correctly, you are reducing its toughness. Pre-cooking, we have two primary ways to do it:

Chemical Methods: Marinades

Sitting meat in a marinade helps tenderise meat by letting acids and/or enzymes start the process of breaking down the connective tissue. This is most effective where the marinade is in contact with the meat – i.e. the surface, so thin cuts make more sense.

Acids – marinades containing acid – that is, lemon juice or wine.

Enzymes – fruit – marinades featuring pineapple, kiwifruit or paw paw.

Mechanical Methods: Beating the crap out of it.

There is a couple of methods available to you here – dependant on the equipment you might have. Essentially the concept is the same regardless – you are working on breaking down the connective tissue into smaller pieces, which in turn you don’t need to bite through to eat.

Hammer Time – what many people are familiar with is the heavy, toothed surface hammer that you use to physically beat the meat into tenderness.

The needler – a machine that either makes very fine cuts all over the meat or literally pincushions the meat, breaking up the less tender tissue.

Cutting it fine – simply cutting meat up into fine cubes is a time tested method of breaking up the tissue and making it more easily broken down.

Cooking Methods

Slow and low is the key here – and for long periods of time.

By cooking cubed meat slowly in a moist (i.e. marinade of wine and a can of tomatoes) you are creating the optimum environment to break down the connective tissue and make the meat essentially break apart.

Cooking meat this long actually can make the muscle fibres themselves tougher, but because you are turning the connective tissue into gelatin, the fibres no longer have anything to hold them together and instead have a silky smooth texture that can be pulled apart with a pair of forks (hence, pulled pork).

105F/40C – 122F/50C –Calpains begin to denature and lose activity till around 105F, cathepsins at 122F. Since enzyme activity increases up to those temperatures, slow cooking can provide a significant aging effect during cooking. Meat should however be quickly seared or blanched first to kill surface microbes.

120°F/50°C — Meat develops a white opacity as heat-sensitive myosin denatures. Coagulation produces large enough clumps to scatter light. Red meat turns pink.

Here are the early stages of juiciness in meats as the protein myosin, begins to coagulate. This lends each cell some solidity and the meat some firmness. As the myosin molecules bond to each other they begin to squeeze out water molecules that separated them. Water then collects around the solidified protein core and is squeezed out of the cell by connective tissue. At this temperature meat is considered rare and when sliced juices will break through weak spots in the connective tissue

140°F/60°C — Red myoglobin begins to denature into tan coloured hemichrome. The meat turns from pink to brown-grey colour.

140°F/60°C — Meat suddenly releases lots of juice, shrinks noticeably, and becomes chewy as a result of collagen denaturing which squeezes out liquids.

Collagen shrinks as the meat temperature rises to 140/60 more of the protein coagulates and cells become more segregated into a solid core and surrounding liquid as the meat gets progressively firmer and moister. At 140-150 the meat suddenly releases lots of juices, shrinks noticeably and becomes chewier as a result of collagen shrinkage. Meat served at this temperature is considered medium and begins to change from juicy to dry.

160°F/70°C — Connective tissue collagen begins to dissolve to gelatin. Melting of collagen starts to accelerate at 160F and continues rapidly up to 180F.

Falling apart tenderness collagen turns to gelatin at 160/70. The meat gets dryer, but at 160F the connective tissues containing collagen begins to dissolve into gelatin. With time muscle fibres that had been held tightly together begin to easily spread apart. Although the fibres are still very stiff and dry the meat appears more tender since the gelatins provide succulence.

NOTES: At 140°F changes are caused by the denaturing of collagen in the cells. Meat served at this temperature med-rare is changing from juicy to dry. At 160°F/ 70°C connective tissue collagen begins to dissolve to gelatin. This, however, is a very lengthy process. The fibres are still stiff and dry but meat seems more tender. Source: Harold McGee — On Food and Cooking

Feel the need to geek out even more?