We just got back from another long weekend up at Little Sandy Bay, and like always, it was magic. We’ve always called it Little Sandy Bay, and it’s been my family’s slice of paradise for as long as I can remember. Driving up there, winding through the hills, it feels like stepping back in time, away from the hustle and into a world where the pohutukawa trees are the real bosses and the rhythm of the tide sets the pace.

Being up there always gets me thinking about the stories held in that land, the whispers of the past carried on the sea breeze. Port Charles isn’t just a pretty spot on the map; it’s a place layered with history, with tales of pioneering spirits, hard graft, and generations who’ve found solace in its rugged beauty. And it got me wondering, how many others who love this place actually know its story? So, I decided to dig a little deeper, to unearth some of the yarns that make Port Charles what it is today. Come with me as we explore the history of this special corner of the Coromandel, from its very name to the families who, like mine, have woven their lives into its fabric. And of course, the ever-present Moehau Range that looms in the background, watching over it all.

Where Did the Name ‘Port Charles’ Come From?

Ever wondered who Charles was, and why he got a whole port named after him? It’s a fair question, and the answer takes us back to the early days of European exploration in New Zealand. Turns out, Port Charles likely wasn’t named after some local legend named Charlie, but rather after Captain Charles Clerke, a significant figure in maritime history.

Captain Clerke was actually Captain James Cook’s second-in-command on his third and final voyage to the Pacific. When Cook was tragically killed in Hawaii in 1779, it was Clerke who took command of the expedition and brought the ships back home. So, while Clerke himself may not have ever set foot in Port Charles, his name carries weight and connects this little bay to a grander narrative of exploration and discovery.1

Now, who exactly decided to name this specific spot after him is a bit of a mystery, lost to the mists of time. It likely happened sometime in the late 18th or early 19th century as European charts of the New Zealand coastline were being drawn up. Back then, naming landmarks after prominent figures was a pretty common practice, a way to honour these individuals and also to lay claim to these newly ‘discovered’ lands.2.

What Was Port Charles Like Before Europeans Arrived?

Before Captain Clerke’s name graced the charts, and long before European settlers set foot on its shores, Port Charles was, of course, Māori land. For centuries, this area, like the rest of the Coromandel Peninsula (Te Tara-o-te-Ika-a-Māui, meaning “the barb of Māui’s fish”), was home to Māori iwi (tribes), who lived in close connection with the land and sea, their lives deeply intertwined with the natural rhythms of this coastal environment. The looming presence of the Moehau Range would have been an integral part of their world, a place of significance and perhaps spiritual connection.

The Coromandel, in general, was traditionally rohe (territory) of various iwi, including Ngāti Hei, Ngāti Maru, and Ngāti Whanaunga. While specific historical records detailing pre-European Māori settlements in the exact location of Port Charles might be scarce in readily available online resources, we know that Māori communities thrived throughout the Coromandel, utilizing its rich resources.3 The Moehau Range, with its challenging terrain and unique ecosystem, likely held special significance as a source of resources, a place of refuge, or a boundary marker.

Think about it: sheltered bays like Port Charles would have been ideal locations for settlements. They provided safe harbours for waka (canoes), abundant fishing grounds, and access to the resources of the surrounding forests. The estuaries and coastlines would have been rich sources of shellfish, and the forests provided timber for building, firewood, and native birds for food.

Māori were skilled navigators and seafarers, and the coastal waterways were their highways. Waka would have been a common sight in these waters, connecting communities and facilitating trade. Imagine the scene: the rhythmic splash of paddles, the calls of seabirds, the scent of woodsmoke from fires on the shore, a vibrant community living in harmony with their environment.

These weren’t just temporary camps; these were established communities with deep knowledge of the land and its cycles. Māori had intricate systems of resource management, ensuring sustainability and respecting the mauri (life force) of the natural world. They understood the seasons, the tides, and the movements of fish and birds, knowledge passed down through generations. The Moehau Range, a constant presence on the horizon, would have served as a natural landmark, a guide for navigation, and a source of weather forecasting knowledge.

It’s important to remember that when we talk about the ‘history’ of Port Charles, we’re not just starting the story with European arrival. There’s a much longer, richer history that precedes that, a history of tangata whenua (people of the land) who were the first custodians of this beautiful place. Acknowledging this pre-European history is crucial to understanding the full story of Port Charles and the Coromandel.

When Did Europeans Arrive and What Drew Them to Port Charles?

The arrival of Europeans in the Coromandel, including areas like Port Charles, marked a significant shift in the region’s history. While Captain Cook and others had charted the coastline earlier, it was in the early to mid-19th century that more sustained European presence began to take hold. What drew them to places like Port Charles? Well, like much of New Zealand at the time, it was a combination of resources and opportunity. They, too, would have been keenly aware of the presence of the Moehau Range, though perhaps viewing it more as a navigational hazard or a source of timber than a place of spiritual significance.

One of the biggest draws to the Coromandel Peninsula was timber, particularly kauri. These magnificent trees, towering giants of the forest, were highly sought after for their strength, durability, and straight grain. They were perfect for shipbuilding, house construction, and all sorts of other uses. And the Coromandel was, and still is in pockets, covered in them.4 Even the slopes of Moehau would have been targeted for their valuable timber resources.

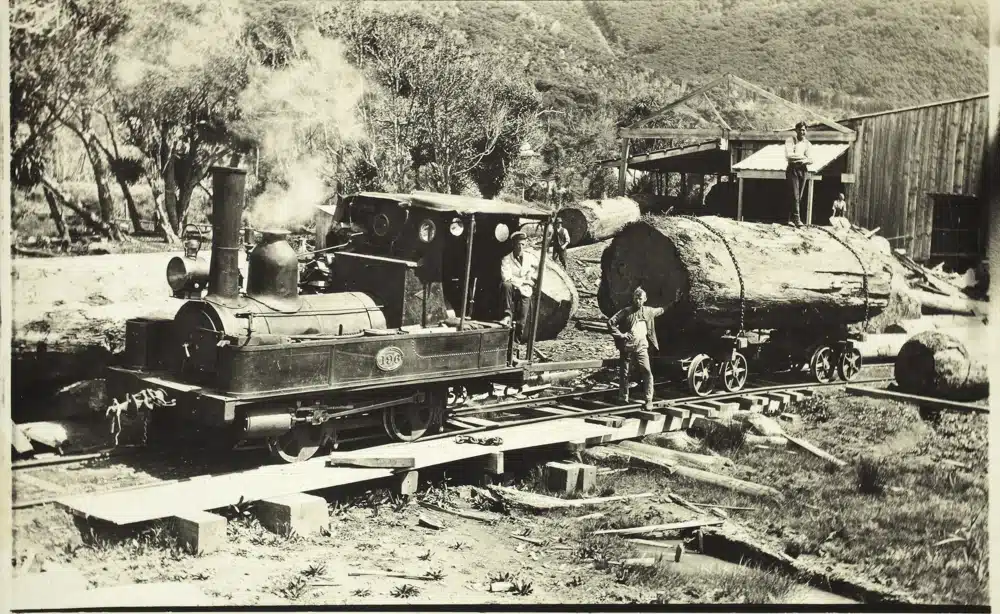

Port Charles, with its sheltered harbour and proximity to vast kauri forests, became a natural focal point for the timber industry. Imagine the scene: ships arriving in the bay, axes ringing through the forest, teams of bullocks hauling massive logs down to the coast. Sawmills would have sprung up, processing the timber and preparing it for shipment, likely down to Auckland and further afield.

The timber industry was a tough and often dangerous business. Felling massive kauri trees, navigating treacherous terrain, and working in remote locations demanded resilience and hard work. The early European settlers in Port Charles would have been a mix of loggers, sawyers, shipwrights, and traders, all drawn by the promise of making a living from the land and its resources.

Beyond timber, there were other attractions too. The sheltered waters of Port Charles offered opportunities for fishing and coastal trade. As settlements grew in Auckland and elsewhere, there was a demand for food and other supplies, and coastal communities like Port Charles could play a role in providing these.

This period also brought challenges and disruptions for Māori communities. Land alienation, resource depletion, and the introduction of new diseases had a profound impact on traditional ways of life. Understanding this complex and often difficult history is essential to appreciating the full story of Port Charles.5

The Rise and Fall (and Rise Again?) of Logging in Port Charles

Logging was, without a doubt, the industry that shaped Port Charles in its early European history. For decades, the sound of axes and saws would have echoed through the hills, as the seemingly endless kauri forests were felled to meet the growing demand for timber, both locally and internationally. It was a boom-and-bust industry, and Port Charles experienced both sides of that cycle. Even the slopes of the Moehau Range weren’t immune to the logger’s axe, though its steeper terrain may have offered some protection to its most remote reaches.

The initial years of logging in Port Charles would have been a period of intense activity. Picture teams of men, often working in harsh conditions, felling giant kauri trees that had stood for centuries. These trees were incredibly heavy, and getting them out of the forest and down to the coast was a massive undertaking, often involving bullock teams and rudimentary tramways.

Sawmills were essential to the logging operation, and Port Charles would have had its share. These mills processed the raw logs into sawn timber, ready for shipping. Life in a logging settlement like Port Charles would have been tough and rugged, centred around the rhythm of the work, the changing seasons, and the challenges of living in a remote location.

As the most accessible kauri forests around Port Charles were depleted, the industry started to shift. Loggers had to venture further inland, into more difficult terrain, to find remaining stands of timber. This made the work even harder and more expensive. The industry was also subject to fluctuations in demand and market prices, adding to the uncertainty.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the kauri forests of the Coromandel were becoming significantly depleted. Over-logging and a lack of sustainable practices had taken their toll. Many logging operations began to wind down, and settlements like Port Charles faced a period of economic decline as their primary industry shrank.

Did Gold Fever Ever Strike Port Charles?

While the Coromandel Peninsula is famously known for its gold mining history, particularly in places like Thames and Waihi, Port Charles itself wasn’t a major gold mining centre in the same way. However, the gold rushes of the late 19th century certainly had an impact on the wider region, and it’s worth exploring whether “gold fever” touched Port Charles in any way. The lure of gold may even have drawn some prospectors to explore the streams and gullies of the Moehau Range, though its rugged terrain would have made such efforts particularly challenging.

The main gold discoveries in the Coromandel were further south, around Thames and then later in Waihi. These areas saw massive gold rushes, with thousands of prospectors flocking to the region in search of their fortune. Towns boomed, infrastructure was built, and the Coromandel became synonymous with gold mining.

Port Charles, being somewhat more remote and less geographically suited to large-scale gold mining, didn’t experience the same level of gold rush frenzy. The terrain around Port Charles is steep and heavily forested, which would have made prospecting and mining more challenging compared to the flatter, more accessible areas further south.

However, it’s likely that some prospectors would have explored the hills and streams around Port Charles, hoping to strike it lucky. Gold is often found in association with certain geological formations, and the Coromandel Peninsula as a whole is geologically rich in minerals. So, it’s not out of the question that small-scale prospecting took place in the Port Charles area.

How Did Port Charles Become a Holiday Getaway?

From a rugged logging and potentially prospecting outpost, Port Charles has transformed into a cherished holiday destination. This transition wasn’t sudden, but rather a gradual evolution, driven by changing lifestyles, improved access, and the enduring appeal of its natural beauty. How did this quiet corner of the Coromandel become the getaway we know and love today?

One of the key factors was the sheer beauty of the place. The sheltered bay, the sandy beaches, the surrounding native bush – these were always there, waiting to be appreciated for their recreational value. As people in cities like Auckland sought escapes from urban life, places like Port Charles, with their unspoiled natural environment, became increasingly attractive.

Early holidaymakers might have been drawn to Port Charles for fishing, boating, and simply enjoying the peace and quiet. Simple baches (holiday homes) would have started to appear, perhaps initially built by locals or those with connections to the area. These would have been basic structures, often built with timber from the local forests, providing a simple base for weekend getaways and summer holidays.

The development of roads played a crucial role. In the early days, access to Port Charles would have been primarily by sea, or via rough tracks. As roads improved, albeit slowly, it became easier for people to reach Port Charles by car, opening it up to a wider range of holidaymakers.

The character of Port Charles as a holiday destination has always been somewhat low-key and understated. It’s not a place with big resorts or bustling commercial centres. Instead, its appeal lies in its relative remoteness, its natural beauty, and its relaxed pace of life. It’s a place where you come to disconnect from the stresses of modern life and reconnect with nature and with family and friends.

Little Sandy Bay and Adlor Hill Road: A Family Story

Now, let’s talk about Little Sandy Bay and Adlor Hill Road – the places that are particularly close to my heart and my family history. I mentioned that Little Sandy Bay is what we’ve always called that smaller bay before Sandy Bay proper, and Adlor Hill Road has a personal connection to my family. This is where the story gets even more special, because it’s about the people who shaped the Port Charles we know and love, on a more intimate, family level.

My understanding that Adlor Hill Road was named by my father (Adams) and other families like the Hills, Kinghorns, and Suttons – that’s fantastic local knowledge, the kind of stories that aren’t written in official history books, but are passed down through families and communities. This kind of naming is typical of how places evolve, how local identities are forged, and how families leave their mark on the landscape.

I imagine my Grandfather and these other families, establishing their baches in this beautiful spot, creating their own little community within Port Charles. Naming Adlor Hill Road – combining ‘Adams,’ ‘Hill,’ and perhaps ‘lor’ as a common suffix or just a bit of fun – is such a wonderfully personal and informal way to name a road. It speaks to a sense of ownership, of belonging, and of shared experience.

Little Sandy Bay, as we call it, likely got its name simply because that’s what it is – a small, sandy bay. Often, these informal place names, the ones used by locals and families, are just as important, if not more so, than the official names on the maps. They reflect the lived experience of the place, the way people interact with it and understand it.

My family’s long connection to this area, owning a bach there for generations, that’s a powerful link to the history of Port Charles. My grandparents, my parents, myself – all spending time in this special place, creating memories, building traditions, and becoming part of the fabric of the community.

These family baches in places like Port Charles are often more than just holiday homes. They are repositories of family history, filled with old photos, mementos, and the accumulated stories of generations. They are places where children grow up, where families gather, and where a sense of place and belonging is nurtured.

The Adams, Hills, Kinghorns, and Suttons – these are the kinds of names that are woven into the local history of Port Charles. They are the families who built the baches, who spent their summers fishing and swimming, who contributed to the community, and who helped to shape the character of the place.

And my personal connection, my annual visits, my childhood memories of Little Sandy Bay – that’s what keeps this history alive. It’s not just about dates and events in books; it’s about personal stories, family traditions, and the emotional connection to a place that runs deep through generations.

So, Adlor Hill Road and Little Sandy Bay aren’t just names on a map; they are part of my family’s story, and my family’s story is part of the story of Port Charles. It’s a beautiful example of how personal histories and local histories intertwine, creating the rich tapestry of a place like this.

How Has Port Charles Changed Over the Years?

Like any place, Port Charles has changed over the years, evolving from its early days as a resource-extraction settlement to the holiday destination it is today. These changes are a reflection of broader societal trends, technological advancements, and the ever-shifting relationship between people and the environment. Let’s consider some of the key ways Port Charles has transformed over time.

One of the most obvious changes is in the landscape itself. The once vast kauri forests have been significantly reduced by logging. While native bush has regenerated in many areas, the character of the forest is different now, with fewer of those giant, ancient trees. This ecological transformation is a legacy of the logging era, and a reminder of the impact of human activity on the natural environment.

The population of Port Charles has likely fluctuated over time, depending on the economic activities of the area and its appeal as a holiday destination. In the early logging days, there might have been a transient population of workers. As logging declined, the population may have decreased. And with the rise of tourism and holiday home ownership, the population likely swells during peak holiday periods.

Technology has had a significant impact, as it has everywhere. Improved transport, communication, and access to information have connected Port Charles to the wider world in ways that would have been unimaginable in the early days. The internet, mobile phones, and modern conveniences have changed daily life, even in a relatively remote place like Port Charles. I remember heading up there last year – for the first time – we actually had cellphone connection! It was both a happy and sad moment. As there are not a lot of places left in NZ where you can be truly ‘offline’ for any period of time, but, I made a conscious effort to leave the phone alone, and the kids had their tablets left at home!

It’s also worth noting the evolving focus on conservation and environmental awareness. In more recent times, there have been initiatives aimed at protecting the natural environment of Port Charles, reflecting a growing understanding of the importance of sustainability. The establishment of the Kiwi Sanctuary near Port Charles was one example of these efforts, aiming to protect and enhance the local kiwi population.

Update regarding Kiwi Sanctuary: It seems the Kiwi Sanctuary has recently been replaced by the Hillary Outdoors Centre. While the Kiwi Sanctuary played a vital role in protecting the local kiwi population, the Hillary Outdoors Centre aims to provide outdoor education and leadership development opportunities for young people, continuing the area’s tradition of connecting people with nature and promoting environmental stewardship.6 It will be interesting to see how the Hillary Outdoors Centre evolves and contributes to the Port Charles community.

Despite these changes, there’s also a sense of continuity in Port Charles. The natural beauty of the place remains a constant attraction. The relaxed pace of life, the strong sense of community, and the connection to nature are still valued by those who live there and those who visit. In many ways, Port Charles has managed to retain its essential character, even as it has adapted to changing times.

A Memory of Moehau.

I remember a time when I was a teenager, climbing up the Moehau Range with my father. He realized one day, having spent a lot of his childhood up there, had never been up the massive range that always sat in the background. So, one day we went to remedy that.

I remember it was a steep climb, hand over foot in many places, and, as we arrived near the top, the entire area had a very ‘strange’ feel to it. As it turns out, we had come up near what I later learnt was a burial ground. It was quite obvious to both of us that it wasn’t an area to be walking into, so we didn’t. It’s a place treated with great respect by local Māori, and rightly so.

The mist had come down a lot on our walk up, so unfortunately, when we got up the top, the view wasn’t very clear. In a moment of wonder though, while we stood there, the clouds pulled back, revealing the view of the Coromandel below, which we both got to appreciate for a couple of minutes before the clouds rolled back in and we were again surrounded by white for the start of the trek back down. That brief glimpse of the Coromandel from the heights of Moehau is a memory I’ll always treasure, a reminder of the beauty and wonder that can be found in this special place. And a reminder of how that mountain has silently watched over Port Charles for countless generations.

Information about Captain Charles Clerke can be found in numerous historical accounts of Captain Cook’s voyages. A good starting point is Cook’s journals, available in many archives and libraries. ↩

This is a common practice in early colonial mapping; examples can be found by searching historical maps and records of the time period ↩

Information about Māori iwi and their traditional rohe in the Coromandel can be found on websites such as Te Ara – The Encyclopedia of New Zealand and in iwi-specific publications and resources. ↩

Information on the Kauri timber industry in the Coromandel can be found on websites like the Department of Conservation (DOC) and in historical texts about New Zealand forestry. ↩

Information on the impact of European settlement on Māori communities can be found in the Waitangi Tribunal reports and academic works on New Zealand history. ↩

Information on the Hillary Outdoors Centre can be found on their official website: https://hillaryoutdoors.co.nz/ ↩