Did you know there are ‘three’ Norths?

Magnetic Declination – What is it?

On this beautiful planet of ours, we have the Geographic North Pole (where Santa lives), Magnetic North Pole – which is where a magnetised compass needle will point towards and for some maps, Grid North. The difference between these two points is referred to Magnetic Declination, or often, just Declination.

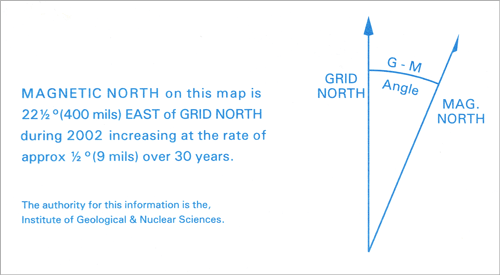

TOPO50 maps are created utilising Grid North. Compasses point to the Magnetic North Pole. This can be a 20-degree difference.

See a potential issue here?

To complicate matters, the Magnetic North changes, dependant both on where you are, and when you are. Mainly, Magnetic North is determined by the earth’s molten outer core. Localised magnetics rocks, kilometres beneath can affect things, but primarily, it’s the magma that determines where the compass needle points. Being molten, it shifts over time, and as a result, the Magnetic Declination is also always changing.

Luckily, on all of LINZ’s Topo50 maps in current production, the Magnetic Declination is clearly marked on the bottom of each map. NOTE: This declination varies from map to map, location to location – for example – in Auckland you are going to have around 21 deg and Wellington is going to be closer to 24. It might not ‘seem’ that much difference – but over a distance, a couple of degrees quickly adds up.

Magnetic Declination – How to compensate

Now that we know that the map we have in our hands is using a different reference for north than our compass is, how do we translate between the two?

Mostly, you will need to take the difference indicated from Geographic North (generally referred to as ‘grid’ north) and magnetic north. But do we add or subtract from our figure?

An easy way to remember is this – if you are taking a bearing ‘off’ the map – you take the number off to get declination. If you are putting a bearing you have made with your compass ‘onto’ the map – you add the figure.

- Off = subtract

- On = Add

For example – according to your Topo50 map (indicating a 22.5 deg declination like above) you need to be heading from your current position at a bearing of 46°. Take the 46, subtract 22.5 (taking a measurement off the map) and you have a magnetic bearing of 23.5°.

Alternatively – taking a bearing of 98° off an identifiable mountain in the difference, we add 22.5 (putting it ‘on’ a map) to give us a grid bearing of 120.5°.

Magnetic Declination – is there an easier way?

Why yes. There is! Instead of having to add or subtract declination each time you convert from grid to magnetic or vice versa when using the compass and putting ‘the red in the shed’, aim the compass needle to the declination required on the outer ring of the bezel.

So, in the example above, you take a grid bearing of 46° Grid, twist the bezel on your compass so the direction of travel indicator is 46°, then turn yourself until the red compass needle is pointing to 22.5°.

Even easier? Get a compass with Declination Adjustment on it. Some of the higher end compasses will have the ability to rotate the outer part of the bezel, usually with the use of a small screwdriver, to permanently ‘dial in’ an areas Declination Adjustment. This means that you simply take the bearing off the map in the usual way, put the ‘red in the shed’, and go.

Caveat: We are discussing several different ways to achieve the same thing. The potential for confusion in communication arises because not everyone does things the same way. It is vitally important then, then whenever you give a bearing out, that you follow it with either ‘grid’ – meaning you have taken it off the map, or ‘magnetic’ meaning you have taken it off the compass.

37° Grid and 37° Magnetic could lead you in two very different directions.